Long Distance Hiking Routes

What makes an interesting long distance hiking route? What are some of the well known trails? Why choose one hike over another? How did they become long distance hiking routes in the first place?

Why a Route is Interesting

To be of interest as a long distance hike, a route is probably over a couple of hundred miles long. Shorter than that, a long distance hiker could easily walk the route without resupplying or applying other special skills and techniques. Thus, it would be plain old backpacking, not long distance hiking. Furthermore, an experienced long distance hiker, well conditioned and familiar with long distance hiking techniques, might finish a 200 mile hike in 8 or 10 days. I think that's just not long enough to savor the experience, to develop the attitudes and feelings inherent in a great long walk.

Of course I also do weekend hikes, day hikes, and even nature observation trips where I hardly walk much at all. And they are quite interesting and enjoyable. But they are so different in so many ways that I consider long distance hiking to be an entirely different sport.

One of the two major aspects of long distance hiking which I treasure is that I do so much Thinking, Introspection, Meditation, and Contemplation, that each long distance hike is life changing. To allow everyday isssues to fade to the background, and properly ponder issues that may radically change one's thinking, months may be required. (This is also one of the major reasons I prefer to hike alone - fewer interruptions to my pondering).

Each route has its own personality - its own attractive features, as well as its own problems. And each hiker has different preferences, so what one sees as an attractive aspect of a particular trail may not appeal to another hiker.

The other major aspect of long distance hiking that I love is thinking about the natural world in which I am immersed. I like to visit many types of ecosystems, and in particular I like to walk between one ecosystem and another. More animals live in such transition zones than in singular ecosystem types because different resources may be obtained from each area. But to me, what's more important than just seeing an animal is considering why that animal lives in a particular ecosystem or transition zone, or perhaps considering why the ecosytem changed. Has the soil type changed, or is the bedrock type or depth changing? I am a person who is driven to think, and the changing natural world along a long distance trail provides me a never ending supply of curious things to puzzle over. So I specifically select trails to have as many ecosystem types and transitions as possible.

Ego is a major reason that others attempt long distance hikes. It feels great to know that you've completed something so incredibly difficult that only a vanishingly small percentage of the population even has a chance of finishing. And though few in the general population will share your enthusiasm for the hike, or appreciate the immensity of its difficulties, when you meet those few, their recognition of your acheivement will create an unbelievable high. If that's what you want, you'll have to pick a trail with which your intended audience is familiar.

Those who hike to socialize may hike on the Appalachian or Pacific Crest Trails, or other popular routes, and thereby meet many other walkers, or may hiker lesser travelled trails with groups.

A hiker choosing a trail will need to trade between a large population near the trail, which means more stores, motels, and other helpful businesses, or a trail through an area of sparse population, whose advantages include more solitude and less disturbance to nature.

I chose the Pacific Crest Trail as my first long distance hike simply because I grew up near it and was familiar with it. And others often choose to hike a particular trail because they already know it.

Some routes have excellent guidebooks and maps, or excellent tread, signage, and maintenance, whereas others may have little documentation and be very difficult to follow. A hiker would choose one extreme over the other depending on whether he considered difficulties in navigation to be an interesting and fun challenge on the one hand, or on the other, a pain in the butt.

If a hiker really likes shelters, or fishing along the hike, or views, or so many other things, he will find some trails to have them and others to be entirely lacking.

Certain trails visit environments that some love and others hate, like deserts or miles of flooded trail. Some routes are famous for their weather, either fair or foul. Most trails or their various smaller sections have comfortable seasons and atrocious seasons. So a hiker will consider whether to walk a particular trail based on the weather and environment during the season in which he intends to hike.

Well Known Trails

Trails also have varying degrees of legal acceptance. In the United States, there are National Scenic Trails, which have been voted on and established by the US Congress. The same law which authorized National Scenic Trails also authorized National Recreation Trails (NRTs). NRTs are not voted on by congress, but approved by administrators in agencies such as the US Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, and etcetera. A state can also develop its own long distance trail, either with much federal cooperation or with little. Some routes have no official standing at all, but have been accepted and walked by the long distance hiking community. The differing degrees of government acceptance can affect the hiking of the various routes.

There are, of course, long distance walks outside the United States, and they too have unique personalities.

The National Scenic Trails

To be a National Scenic Trail, a route has to have been approved by the US Congress. Before that happens, the trail is typically largely built and there are a large number of people building, maintaining, organizing, and hiking it. Most of the National Scenic Trails are therefore recognized long distance walking routes.

| The National Scenic Trails | Agency | Year Approved |

Length (miles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appalachian National Scenic Trail | NPS | 1968 | 2,100 |

| Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail | USFS | 1968 | 2,600 |

| Continental Divide National Scenic Trail | USFS | 1978 | 3,100 |

| North Country National Scenic Trail | NPS | 1980 | 4,600 |

| Ice Age National Scenic Trail | NPS | 1980 | 1,200 |

| Florida National Scenic Trail | USFS | 1983 | 1,400 |

| Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail | NPS | 1983 | 700 |

| Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail | NPS | 1983 | 440 |

| Arizona National Scenic Trail | USFS | 2009 | 800 |

| Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail | USFS | 2009 | 1,200 |

| New England National Scenic Trail | NPS | 2009 | 220 |

AZT Completion Marker

The Appalachian National Scenic Trail

The Appalachian Trail is the most popular of the National Scenic Trails. Each year, thousands of people attempt to hike its entire length, thousands more try to hike long sections, and untold masses take day and short overnight hikes. Maintaining the trail is also popular, with many clubs taking regular outings to maintain their section of the trail.

There are as many reasons to hike the AT as there are hikers, but I'll try and outline some of the reasons people prefer to hike this Trail. First, the AT runs through the highly populated east coast states, so many people have been introduced to the AT on some day hike or country drive. That gets some of them thinking, and some of those eventually get around to hiking it. Second, hiking the AT is logistically easier for many people than hiking other routes. The AT runs through the most populated part of the United States, so people who live there don't have to travel far to start their hikes. There are stores, restaurants, hostels, and other establishments that cater to hikers in just about any town near the AT. The AT is the only long distance route in the United States with such an extensive network of supporting businesses. The AT is extremely well maintained, with a wide, clear treadway, blazes virtually always in sight, signs explaining most intersections, etcetera. There are rain shelters for resting along the AT every 8 miles or so. There are many people hiking the AT, so one can socialize at shelters and while hiking. If a hiker were to get in some sort of trouble on the AT, the many other hikers there might be able to help. With so many hikers, there are always several guidebooks and map sets updated and in print.

What appeals to one hiker might repel another. And with respect to the AT, the same reasons some hikers like it are why others don't. Some people don't want the crowds on the AT, don't want a blaze on every other tree, don't want all the wildlife scared away by the constant stream of hikers, want some solitude rather than constant company, and etcetera.

If I had six months available for a big hike, I personally would choose many other routes over the Appalachian National Scenic Trail. Most of the AT is in one pine-hardwood ecosystem type, so there's little change. Further, with so many hikers, wildlife is constantly flushed away from the trail. With little change, and few wild animals, and with the constant stream of other hikers, much of my pondering of nature and my meditation, my two primary reasons for long distance hiking, is destroyed. Most of the AT is deep in forest, so there are few views. When there are views, they are mostly of rolling forests. I love the views of different geology, of historic features, etcetera, on the western trails, and the views from the AT just can't compare. Although most of those I've met along the AT were wonderful, with such a large population, there were jerks too. And each huge jerk did much to deflate the high I derive from my hiking. So I like the other trails much more than the AT.

Given that there are many times more hikers on the AT each year than on all the other United States routes combined, I'm certainly in a small minority. The point is, not everyone likes the same stuff. And I can go hike the kind of routes I like, while lovers of the AT can walk it.

As an added bonus, by hiking the AT they'll avoid my grouching.

Unless they read this book.

Some people feel that the Appalachian Trail is not long enough. After all, the termini are at random mountains in Georgia and Maine rather than at the borders of the United States like some other trails. Some of these people hike the Eastern Continental Trail: They start at Key West, Florida, and walk the highways to the Everglades. Then they walk the Florida Trail to the Alabama border north of Pensacola. After several days of highway walking, they pick up and follow the Pinhoti Trail across Alabama and Georgia to The Benton Mackaye Trail. They follow the BMT for a few days to the southern terminus of the AT at Springer Mountain, and follow that north to Mount Katadyn, Maine. They then continue to the Canadian border, and perhaps to Cape Gaspé.

Some people feel that the Eastern Continental Trail is for wimps: Why stop at the Canadian border? They may hike the International Appalachian Trail. They would start with the ECT, then continue across Canada to Cape Gaspé, Quebec, then take a ferry to Belle Isle (Newfoundland and Labrador), and hike across that. After all, these are part of the Appalachian Mountain Range. For good measure, they may go hike across various Atlantic Ocean islands and European mountain ranges that before plate tectonics and continental drift rearranged the world were part of the Appalachians.

The Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail

The PCT is the second most popular of the National Scenic Trails. It receives perhaps 1 tenth as much traffic as the AT, so hikers have a better chance at seeing wildlife, and having moments of solitude than on the AT. The PCT has good tread, and usually has good markings at trail intersections, so it's easy to follow so long as it's not buried in snow. (Most years at least a few miles are snowed in during the season that long distance hikers pass through.) The PCT is graded for stock, so there are no steep climbs or dangerous exposures. It visits a wide variety of different ecosystem types. The PCT travels miles along ridgelines with outstanding views. There are good guides and maps available.

It seems I listed no negatives. Maybe that's because I consider the PCT to be the best of the US long distance trails, with no close runner up. It's that good.

And for what it's worth, I've spoken with many Triple Crowners (People who have hiked all of the AT, the CDT, and the PCT.) and they all agree that the Pacific Crest is the best of the lot.

The Continental Divide National Scenic Trail

The CDT is widely regarded as the toughest of the National Scenic Trails. Some years it has enough snow to make hiking it in one season all but impossible. Many stretches have little water, or poor quality water. Trail towns and supplies are often quite far apart, making packs heavy. Relatively few people hike it, making for more solitude and less social interaction.

The CDT crosses some beautiful, wild land, with many ecosystems, much wildlife, interesting geology and history. But perhaps the biggest reason people hike the CDT is precisely that it is so difficult, so completing it is the achievement of a hiking lifetime.

Moreso than on any other National Scenic Trail, CDT hikers feel free to hike parallel to the official CDT on a route of their own design while still considering their walk a CDT thruhike. Perhaps the next valley over has more water, better views, etcetera. Perhaps the official route takes a huge loop, and the hiker short cuts the loop to complete a hike between Mexico and Canada in one season. Other CDT hikers will not criticize but revel in these choices.

It seems odd to me that anyone would criticize someone who had walked thousands of miles, but...

Snobbish 'White Blazing' Appalachian Trail hikers, at the other extreme, would consider anyone taking an alternative route to some beautiful spot to be a 'Dirty Blue Blazer', while someone who followed a road for a few miles would be considered the lowest of the low, the scum among scum, a 'Yellow Blazer'.

Those of us who would roll our eyes at these egotistical jerks have developed our own acronym: HYOH, or 'Hike Your Own Hike'. After all, some of us are out here to soak in all the beautiful stuff, not to follow someone else's dream.

Some people choose to extend their CDT hike into Canada. The Great Divide Trail continues a few hundred miles north along the Continental Divide before petering out.

The North Country National Scenic Trail

The 4600 mile North Country Trail runs through the northern tier of states in the eastern half of the USA. Its western terminus is at Lake Sakakawea State Park, North Dakota, on the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, and the Eastern terminus is at Crown Point State Historic Site, New York. This is just a few miles from the Long Trail of Vermont. A connector is planned to the Long Trail, and using that, to the Appalachian Trail.

| State | Miles | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| North Dakota | 475 | Garrison Diversion Project Canals |

| Minnesota | 775 | Kekekabic, Border Route, & Superior Hiking Trails |

| Wisconsin | 200 | Saint Croix National Scenic Riverway |

| Michigan | 1,150 | Shore to Shore Riding-Hiking Trail |

| Ohio | 1,050 | Buckeye Trail, Miami & Erie Canal |

| Pennsylvania | 265 | Baker Trail |

| New York | 625 | Finger Lakes Trail, Black River & Erie Canals |

The Ice Age National Scenic Trail

The Ice Age Trail is entirely in Wisconsin. Its termini are at Potawatomi State Park, Door County, and Interstate State Park, near St. Croix Falls. It follows the terminal moraine of the last ice age, and features glacially created terrain, such as kettles, potholes, eskers, and glacial erratics. About 600 miles are complete of 1200 planned. In 2008, the temporary trail included 467 miles of hiking paths, 103 miles of multi-use trails, and 529 miles of roads and sidewalks. Hiking and snowshoeing are the primary modes of travel. There is a 10 mile Timms Hill National Side Trail to Wisconsin's highest point. National Side Trails are an obscure product of the National Trail Systems Act: There are only 2.

The Florida National Scenic Trail

The Florida Trail is unique among the National Scenic Trails in that during the best season to hike it, roughly January through early March, the other NSTs are partly buried in snow. (A long winter hike on them would not just be a matter of getting snowshoes or back country skis: Resuppy stores being closed and avalanches are issues, among others.) The Florida Trail is among the best for seeing wildlife: Birds, mammals and reptiles are plentiful in Florida's backcountry. The geology and geography is quite interestng. The trail is well marked. There are few hikers on the Florida Trail.

Some downsides to the Florida Trail are that the winter days are short and nights long: Each morning I did hours of reading in my hammock by headlamp waiting for the sun to rise. Many miles of the trail will be flooded even during the driest season, and wading them is slow and tiring. The typical thru hiker can expect some long, cold rainstorms, and being soaking wet for days is not fun. Finally, many miles of the Florida Trail are routed on highways, and though there is little traffic on most of them, it's no fun to walk a paved road and beat it into the weeds to allow traffic to pass.

I loved the Florida Trail and returned for a second long hike. I saw a great deal of wildlife, and even an inch of difference in elevation could radically change the plants and animals from one area to another. Farms, swamps, lakes, dikes, etcetera, each had their own plant and animal communities. The limestone bedrock had many interesting fossils. There was plenty of time for contemplation. And as for the highway sections? I did my best to skip them by hitchhiking.

The Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail

The Potomac Heritage Trail is a system of trails along and branching from the Potomac River from Chesapeake Bay north and west through Washington DC to Pittsburg. It crosses the Eastern Continental Divide. Sometimes there are paths on both sides of the river. It crosses the Appalachian Trail and the Tuscarora Trail. There are connecting trails in the Green Ridge State Forest, and the Washington and Old Dominion Trails connects at Arlington. It is partly a paved bike path, and partly gravel or dirt walking paths. There are designated campsites about every 7 miles, and towns most walking days. Parts of the trail are along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Towpath, The Mount Vernon Trail, and the Laurel Highlands Trail. With various side trails and planned trails, the system may total 800+ miles. However, some trail sections are in parallel, and some branch to the side, so a through hike might be substantially shorter.

The Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail

The Natchez Trace is a 444 mile scenic highway. Commercial traffic is prohibited, and entrances are placed to make its use inconvenient for commuting. Still, plenty of big campers and cars full of tourists speed down the highway. I can't imaging that walking its length would be much fun. Along the highway, in 4 segments, are 60 miles of trail. The right of way is not wide enough that a walker could remain out of sight or earshot of the highway traffic. And though people do bike its length, the shoulders are so narrow that as a biker I would be afraid of the huge RVs winding their way down its curves. Rumor has it that congress actually intended to make the Natchez Trace a National Historic Trail, and that the Scenic designation was a mistake. So the Natchez Trace is really not a popular long distance walking route.

Nevertheless, the Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail ought to be of interest to hikers because...

In the days when the Mississippi River drainage was first settled, it was common that once every year or two settlers would build a large raft of timber and load it with their farm produce, animal pelts, and whatever else they wanted to trade, then float down the river system to the mouth of the Mississippi, then sell the raft timbers, produce, etcetera, then buy whatever they needed, then walk back home. The Natchez Trace is one of the routes they walked. Every bandit and gambler along the way knew that virtually every northbound walker had money and valuable supplies. So getting through without being ripped off was quite an adventure. And it was how they survived from year to year, not a vacation like for today's hikers. It's an important historic long distance walking route that far predates most other National Scenic Trails.

The Arizona National Scenic Trail

The 800 mile Arizona Trail runs from the Utah to the Mexican borders. It passes through Flagstaff and east of Phoenix and Tucson. Highlights include the Grand Canyon, the Mogollon Rim, some sky island ranges, and the Arizona deserts. Good water is occasionally difficult to find, but there is an up to date water report on line.

The Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail

The Pacific Northwest Trail runs 1200 miles from the continental divide at Glacier National Park west, just south of the Canadian border, to the Puget Sound, which it crosses by ferry, then passes over the Olympic Range, through the Hoh Rain Forest, to the Pacific Beaches. Highlights include visiting many different ecosystem types. Some bushwhacking and navigation difficulties on little maintained trail sections are to be expected.

The New England National Scenic Trail

The 215 mile New England National Scenic Trail includes most of the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, Mattabesett Trail and Metacomet Trail. It is sometimes called the Triple-M Trail System. No camping is allowed along the length of the New England Trail, so it's hard for me to imagine how one would do a long distance hike. And no one who has completed it has talked to me about it. So I'll call it a bust as a long distance hiking route too.

The National Historic Trails

Although National Historic Trails are authorized under the National Trails System Act along with the National Scenic Trails, National Historic Trail status does not imply that the US Government intends to develop the route as a corridor that can be travelled now or in the future. Rather, it is intended that where roads cross an historic route, interpretive displays will help motorists understand the geography and significance of the historic route. The National Historic Trails include exploration routes and wagon roads, etcetera, which had a significant effect on the settlement of the US. Much of the length of the National Historic Trails is on private property with no current easement or right of way for travel, so hiking them would be trespassing. Also, they don't necesarily travel in corridors that are beautiful or otherwise interesting, so certain portions might not be appealing as long distance hiking routes.

The National Recreation Trails

National Recreation Trails were also authorized under the National Trails System Act of 1968. Unlike NSTs and NHTs, they do not require a congressional vote for establishment: NRT status can be conferred by administrators of the agency which manages the land on which they lie. There are many more NRTs than NSTs and NHTs combined. But most are far too short to be considered long distance trails. Here are some NRTs popular with the long distance hiking crowd...

| A few long National Recreation Trails | |

|---|---|

| Length (miles) |

|

| Pinhoti National Recreation Trail | 335 |

| Sheltowee Trace National Recreation Trail | 315 |

| Ouachita National Recreation Trail | 223 |

| Ozark Highlands National Recreation Trail | 218 |

| Idaho Centenial National Recreation Trail | 900 |

The Pinhoti National Recreation Trail

Some people feel that the Appalachian Trail is just not tough enough. Or perhaps they want their walk to begin and end at the borders of the United States. Or to and from the sea. Or beyond. So they start at the southern tip of Florida, and walk the highway bridges up through the Keys to the Everglades, then the Florida Trail up to Alabama, then highways and the Pinhoti Trail and Benton MacKaye Trail to the AT, then the AT, then more trails to Canada and perhaps beyond...

The point is that the Pinhoti Trail covers most of the distance between the Florida Trail and the Appalachian Trail. And that's a major reason why it's hiked through. It also has ecosystems quite like the AT, and some shelters, but with much less traffic. So if you liked the AT, but thought it was overused, the Pinhoti is a good option.

The Sheltowee Trace National Recreation Trail

The Sheltowee Trace Trail is mostly in the Daniel Boone National Forest and mostly in Kentucky. Sheltowee is one of Daniel Boone's Indian nicknames, and means 'Big Turtle'. It refers to an incident when he hid from a war party submerged in a creek and breathing through a reed. The trail is primarily open to hiking, and has typical eastern forest ecosystems.

The Ouachita and Ozark Highlands National Recreation Trails

These are long trails mostly in Arkansas. The ecosystems are much like the AT; mixed hardwood and conifer forest on rocky hills. The Oauchita has some shelters, and traffic is light enough on both trails for wildlife viewing and solitude.

Ouachita Trail Sign

The Idaho Centennial National Recreation Trail

The Idaho Centennial Trail runs north south the entire length of Idaho.

The developing Great Eastern Trail

The Great Eastern Trail is an example of a trail under development. Its corridor is generally west of the Appalachian Trail. It should offer the same types of ecosystems as the AT without the overuse problems. It will be about 1600 miles. Its termini will be at the northern terminus of the Florida Trail and on the North Country Trail. It will briefly join the AT and the Potomac Heritage Trail, and uses several trails which are significant long distance routes in their own right.

| Great Eastern Trail | |

|---|---|

|

Florida Trail Terminus Alabama State Line |

|

|

Gap - Road Walk to Pinhoti at Flagg Mountain,

largely private lands Alabama 60 Miles |

|

|

Pinhoti National Recreation Trail,

Flagg Mt Terminus to Chattahoochee NF Alabama, Georgia 137 Miles |

|

|

Gap NW Georgia to Tennessee state line,

largely National Forest Georgia |

|

|

Cumberland Trail Tennessee 265 Miles, 126 complete |

|

|

Pine Mountain Trail Kentucky 98 Miles |

|

| Gap | |

|

Appalachian Trail, near Pearisburg, Virginia 21 Miles |

|

|

Allegheny Trail West Virginia 42 Miles |

|

|

Headwaters Section 165 Miles, 158 complete |

|

|

Tuscarora Trail 132 Miles |

|

| Western route | Eastern route |

|

Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath West Virginia |

Tuscarora Trail West Virginia, Pennsylvania |

|

Green Ridge State Forest trail system West Virginia |

Standing Stone Trail Pennsylvania 78 Miles |

|

Sections 1 through 8 of Mid State Trail Pennsylvania |

Greenwood Spur, Mid State Trail Pennsylvania |

|

Sections 9 through 20, Mid State Trail 322 Miles Pennsylvania |

|

|

Crystal Hills Trail: a branch of the Finger Lakes Trail New York 48 Miles |

|

|

Terminus at the North Country Trail New York |

|

Unofficial Trails

The Grand Enchantment Trail

The Grand Enchantment trail runs between Phoenix, Arizona, and Albuquerque, New Mexico. It is an example of a trail which has no government recognition at all. It was invented by Blisterfree, a long distance hiker. The trail visits the pine forests atop the mountain ranges, the deserts below, all the transition zones in between, and actually travels in the water of several riparian tracts in the deserts. Its ecological diversity is outstanding. It also visits old mining districts, ranches, and Indian sites, so its history is intriguing. Blisterfree created great maps and guides, but the route is often overgrown with thorns and also difficult to navigate. It's great for a very advanced level of hiker who wants the challenge and solitude of a little travelled route. It has apparently been a preview of hell for some others.

The Hayduke Trail, in Utah and Arizona, is another example of an unofficial trail.

Trails Outside the United States

There are long walking routes all over the world. One might choose to hike them for their historical or spiritual significance, or for their unique ecosystems, or for an infinite variety of other reasons.

The Camino de Santiago

The Camino de Santiago is a system of Catholic pilgrimage routes from anywhere in Europe to the city of Santiago in northwestern Spain. Its religious significance is that the bones of Saint James, the apostle, are believed to be interred in the cathedral there. Furthermore, during the 1200 years in which the camino has been walked, hundreds of churches have been built for or by the pilgrims. So visiting the churches, and ultimately, the cathedral, has religious meaning to many walkers. With so many pilgrims and religious sites, some hope to have a spiritual awakening. Art and architecture are also reasons for walking, with many works located on the route for pilgrims to see. There is much of historic interest, old castles and churches, city walls and museums, bridges and aqueducts, each reminding us of the history of Spain, of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, of the Crusades and the Spanish Reconquest, and of so much other history. There are hostels where the pilgrims can stay each night, and launder their clothes and shower. The camino has a great social aspect, with many walkers from all over the world communing while walking, while staying in the pilgrim hostels, and while eating. The routes are marked with scallop shell blazes.

Camino de Santiago

Salamanca Roman Bridge and Cathedral

Pilgrimage routes to other famous Catholic sites in Europe also exist and are marked with scallop shells.

Europe's GR trails

There is a system of trails crossing Europe in all directions. They are numbered GRxx, where GR stands for Grande Randonnée, Grote Routepaden, Grande Rota, Gran Recorrido, etcetera, all meaning 'Big Trail'. They are marked with red and white blazes. Lodging and meals are available at regular intervals. Costs are sometimes higher than the pilgrimage routes because pilgrim facilities are often subsidized.

The National Trails of the UK

In the UK there are National Paths, and other Public Paths, which allow one to walk virtually anywhere. Some people walk just a few miles, while others walk the length of the island. Along the way are many historic sites and beautiful scenery. Also, there are many towns where lodging and supplies can be bought. The following table shows fifteen maintained by the National Trails organization, but there are many others with good guidebooks and scenery as nice as those listed.

| National Trails of the UK | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cleveland Way | 110 miles | England |

| Cotswold Way | 101 miles | England |

| Glyndŵr's Way | 135 miles | Wales |

| Hadrian's Wall Path | 84 miles | England |

| North Downs Way | 153 miles | England |

| Offa's Dyke Path | 177 miles | Wales, England |

| Peddars Way, Norfolk Coast Path | 93 miles | England |

| Pembrokeshire Coast Path | 185 miles | Wales |

| Pennine Bridleway | 119 miles | England |

| Pennine Way | 267 miles | England, Scotland |

| The Ridgeway | 86 miles | England |

| South Downs Way | 99 miles | England |

| South West Coast Path | 630 miles | England |

| Thames Path | 183 miles | England |

| Yorkshire Wolds Way | 79 miles | England |

Generally speaking, routes in Europe visit civilization much more frequently than American long distance hikers are accustomed to.

The Te Araroa of New Zealand

The Te Araroa (long walk) runs the full length of New Zealand. Along it, one sees beaches, rain forests, meadows, rivers, and all of the other rich natural scenery New Zealand offers, and well as the unique flora and fauna which has evolved there.

How Long Distance Routes Develop

The typical story of the origin of a long distance route is that someone was looking at a large scale map of public lands and noticed that there was a nearly continuous corridor of public land between two places. Maybe they then walked it themselves, or involved others. If more people got excited about it, maybe they built some trail, lobbied for recognition, or prepared a guidebook or maps, etcetera. Once enough of these activities had been done, perhaps the state or national government gave official recognition to the trail. At the same time, perhaps a few long distance hikers would decide to walk it. And then, depending on their reports, maybe the community of long distance hikers would decide the trail was outstanding enough that some would prefer to hike it over the existing favorite routes. If so, it might join the ranks of the commonly walked long distance routes.

How the National Scenic Trail System Developed

Benton MacKaye first thought up the idea which became the Appalachian Trail in 1921. The idea for the Pacific Crest Trail first occurred to Catherine Montgomery in 1926. Both were developed over many years with the help of many people. By the 1960s, both were fairly complete, and just a few people had hiked their entire distances. But the spirit of the 60s brought on both more willingness to attempt such hikes, and the desire to create a legal framework to manage these trails, and perhaps others.

The US Congress approved the National Trails System Act or Public Law 90-543 in 1968. This law created the National Scenic Trails, discussed here, as well as the National Historic Trails and the National Recreation Trails. The Pacific Crest Trail and the Appalachian Trail existed and had congressional approval before 1968, but the 1968 Act was significant in that it provided a framework under which the trails would be managed, and under which other trails could be added to the system. Essentially, when congress admits a trail to the system, it assigns a lead US Government Agency, such as the Park Service or Forest Service. The lead agency assigns a single ranger to coordinate the various activities and landowners as required to build and maintain the trail. So with a map, an agency, and a ranger, so far as the congress is concerned, the trail exists and no more action is required.

The reality is quite different. The map the congress approved may show the route traversing private property or government land on which the public is not allowed, such as public water supply watersheds. At this point, walking the congressionally approved route would be criminal trespass in these areas, as the route is merely suggested, and congress did not specifially create an easement allowing access across these lands. Permission to cross must be obtained by purchase, donation, etcetera. There may not be trails or roads along the entire route, and if there are, they may not be appropriate for the intended mode of travel (typically walking, use of pack and saddle stock, or bicycling). Water may not be available at reasonably short intervals. There may not be appropriate crossings of busy highways, rail lines, and etcetera. The route may cross ecosystems which would be very negatively impacted by large volumes of hikers. Alternatively, the suggested route may be over soils that cannot support a durable hiking surface. For each of the discussed points, an agreement must be reached, or the trail must be rerouted or redesigned to support the traffic expected on the newly designated trail. There are two important points: the route and various other aspects of the trail will continue to evolve after congressional designation, and a huge amount of work must be done after congress votes.

And even if the government already has a corridor with appropriate easements and a trailbed in place, at least two more groups must come in to being to make the route a success. A group that works alongside the government, raising funds, negotiating land purchases and easements, building and maintaining trail, and etcetera is required because public support must be demonstrated to keep government support intact, and because goverment resources don't cover all of the work which needs to be done. The second group is the hikers. Hikers on the trail also demonstrate that there is support for the route. They also do much to keep the trail open, packing down the tread, pushing overgrowth aside, and etcetera. And, dedicated hikers often provide directions and explanations of a trail's significance to other visitors to the trail corridor.

Trail Associations and Trail Managers

Most of the National Scenic Trails and some of the others have an association which helps to manage it. As previously discussed, the National Scenic Trails each have one government employee managing it. Other employees come and go with the availability of money for certain projects, but they don't stay with the trail for the long term. It takes more people to do all of the things involved in managing the trail. The additional people come from the trail association. In this section, the work of the government trail managers and the associations are discussed together, since the work is done cooperatively.

| Some National Scenic Trail Primary Partners | |

|---|---|

| Appalachian National Scenic Trail | Appalachian Trail Conservancy, Appalachian Mountain Club |

| Continental Divide National Scenic Trail | Continental Divide Trail Alliance |

| Florida National Scenic Trail | Florida Trail Association |

| Ice Age National Scenic Trail | Ice Age Trail Alliance |

| North Country National Scenic Trail | North Country Trail Association |

| Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail | Pacific Crest Trail Association |

Advocacy

The United States is a democracy, with rule by the majority. Yet long distance hikers are a tiny minority. To keep the trails we have protected from other interests, and to keep funding coming to continuously improve our trails, people need to advertise, visit congress, provide information, make budget requests, go to meetings, write and distribute brochures. We need to keep congress, businesses, and people excited about and in favor of our trails, and and keep them providing funds, labors, etcetera.

And none of these groups are small or simple. National Scenic Trails cross thousands of National Park Services areas, National Forests, Wildlife Refuges, BLM areas, state and local parks, and private lands. Just one break in the trail seriously degrades the experience of walking across America, so every land manager and owner must cooperate to keep the trails alive. Every member of congress has a different opinion about something, so it's quite a trick to keep them all in favor of and voting for the trails. Even moreso, private landowners have radically different priorities. If the land at the trail is a large part of their assests, they have a great deal to lose. Ensuring they are well treated and keep positive attitudes about the trail is a big job. And every private landowner has a different financial situation, a different shedule for buying, selling, building on, or exploiting their land, and a different outlook on the trail. All of these people must be convinced to cooperate if the trail is to work.

Managing a Trail Corridor

Trails cannot be treated as an entity independent of everything around them. If, for example, a corridor 10 feet wide was purchased and the trail ran right down the middle, houses and industries might be built right next to the trail. One or two might not create huge problems, but if you had to walk days with no clean streams to drink from and no place to camp, the trail might not be possible to walk. And who would want to walk such a trail for months at a time? We want lakes and streams off the trail to camp and rest at. We want unspoiled views and peace and quiet. We want wildlife to see occasionally.

These goals are accomplished by either protecting the existing corridor or moving the trail to a nicer corridor.

Protecting the Existing Corridor

Some lands along trails are already protected because they are already federal lands designated as parks, wildernesses, etcetera.

Since National Forests and BLM lands are shared between recreation and exploitation, someone must review exploitation projects to ensure they don't negatively impact the trail too much. If timber is to be cut, for example, perhaps the trees within sight of the trail can be left to provide a pleasant walking experience. Where there are views from the trail, perhaps mine and timber harvests can be limited to protect those views. Since streams crossing the trail are drinking water sources, projects upstream can be controlled to limit water pollution.

Private and local government lands along the trail corridor must also be monitored. Any type of development threatening the trail experience must be predicted and addressed. Lands may then be bought (more expensive) or easments must be arranged either for the trail itself to pass through or to limit development within sight of the trail. This task of predicting what a vast array of different land owners may do with their property, tracking their land parcels and the priorities for which to purchase first, etcetera, is a huge job.

About 200 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail, for example, are on private land. Most of the private landowners own less than a mile of the trail. And hundreds of other parcels are close enough to the trail to be of concern. All of those land parcels must be mapped and tracked, the owners must be contacted, funding must be found, purchases or easments negotiated, etcetera.

Relocation

A trail may have been located in a certain place largely because roads and trails already existed there. It might not have been the nicest location in the first place. Or, development may have degraded the existing corridor.

When it is determined that a certain section of trail is inadequate and / or that a much better parallel route is possible, a great deal of work must be done to consider moving the trail. Finding a nicer location requires that someone, professional or volunteer, must notice a new route superior to the old. Then, the feasability of the new route must be studied. Will the soil too rocky or muddy? Will the environment or local wildlife be devastated by the new trail? Who owns the land on the new route and are they willing to sell or allow the trail on their property. Who will pay for the land and trail construction? Would it be better to improve the old route than to build the new? If the new route is to be built, grants must be applied for, lands bought, trail crews organized, etcetera.

When it is determined that a certain section of trail is inadequate and / or that a much better parallel route is possible, a great deal of work must be done to consider moving the trail. Finding a nicer location requires that someone, professional or volunteer, must notice a new route superior to the old. Then, the feasability of the new route must be studied. Will the soil too rocky or muddy? Will the environment or local wildlife be devastated by the new trail? Who owns the land on the new route and are they willing to sell or allow the trail on their property. Who will pay for the land and trail construction? Would it be better to improve the old route than to build the new? If the new route is to be built, grants must be applied for, lands bought, trail crews organized, etcetera.

Trail Crews

Sometimes new trail sections must be built, and trail crews spend even more time maintaining existing trails. Bushes grow over trails and must be lopped back, trees fall over trails and must be cut and removed, trail treads wash out and must be rebuilt, signs and kiosks need to be installed and replaced... The maintenance tasks are endless. Some trail crews belong to the local land management agency, others are conservation corps who maintan trails within a certain area. Still others are parties from clubs or companies who complete one project. Trail associations have their own crews and volunteers too. Someone must coordinate these crews so they work on the most critical sections, and in some cases, tools, training, transportation and guidance must be provided.

Trail Budgets

Of course, it costs money and time to do all this work. Money comes from membership dues, donations, state and local governments, and the federal government. Governments and people will be more willing to fund the trails if they see they are not alone, that others are contributing too. This is a good reason to maintain some trails, and to join or donate to some trail organizations. Here are some anticipated / requested figures for the Pacific Crest Trail to give an idea what a trail's budget looks like:

| Pacific Crest Trail Annual Budget: | |

| About 100,000 volunteer hours, valued at $20/hour: | 2,000,000 |

| Privately raised dollars: | 1,500,000 |

| Government Administration of LWCF Land Purchases: | 250,000 |

| Land and Water Conservation Fund Land Purchases: | 15,000,000 |

| USFS Administration of PCT: Full time PCT Manager, Planning, Optimal Trail Location Reviews, Cost Share with PCTA for Volunteers, Trail Maintenance and Construction, Education, Management and Operations, and Youth and Corps Trail Crews |

2,000,000 |

| Bureau of Land Management Trail Maintenance: | 300,000 |

| National Park Service Trail Maintenance: | 200,000 |

| $21,250,000 | |

|---|---|

Land and Water Conservation Fund

A portion of the money the US Government recieves from offshore oil leases is put into the LWCF. Some of the LWCF is used is used to buy lands for conservation. Land can be bought for wildlife refuges, to fill in gaps in wildernesses, and other conservation purposes. Of interest to us is that land can be bought for the National Scenic Trails. The land can either be the trailbed itself, or land off to the side that is necessary to maintain an unspoiled trail experience. For example, lands that can be seen from the trail can be purchased to protect unspoiled views. If other conservation goals are supported by purchasing a certain plot of land, so much the better. If buying out a mine before it's developed, for example, protects the trail, supports clean water, and protects endangered animals, so much the better. Though lands are also bought with donations, the Land and Water Conservation Fund is a key source of funds for protecting and developing the National Scenic Trails.

A portion of the money the US Government recieves from offshore oil leases is put into the LWCF. Some of the LWCF is used is used to buy lands for conservation. Land can be bought for wildlife refuges, to fill in gaps in wildernesses, and other conservation purposes. Of interest to us is that land can be bought for the National Scenic Trails. The land can either be the trailbed itself, or land off to the side that is necessary to maintain an unspoiled trail experience. For example, lands that can be seen from the trail can be purchased to protect unspoiled views. If other conservation goals are supported by purchasing a certain plot of land, so much the better. If buying out a mine before it's developed, for example, protects the trail, supports clean water, and protects endangered animals, so much the better. Though lands are also bought with donations, the Land and Water Conservation Fund is a key source of funds for protecting and developing the National Scenic Trails.

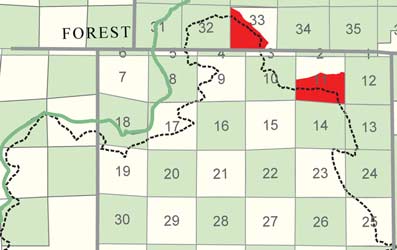

| PCT Proposed Land Buy |

|---|

Note how much private land (white) the PCT (dashed) crosses in this area. National forest land is green, and proposed buy is red. $1.3 million, 659 acres, northern California.

|

Progress is slowly being made. Not so long ago, for example, about 300 miles of the Pacific Crest Trail was on private lands and unprotected. Today, that figure is closer to 200 miles. We need to support these purchases to avoid developing gaps in our National Scenic Trail System.

| Land and Water Conservation Fund

2014 Budget Request |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Scenic Trail | US Forest Service | National Park Service | Bureau of Land Management | Fish and Wildlife Service | Total |

| Appalachian Trail | 6 Tracts 1,168 Acres $4,800,000 NC, TN, VA, VT |

2 Tracts 374 Acres $4,350,000 PA, TN |

None | 1 Tract 3,129 Acres $4,300,000 PA |

9 Tracts 4,671 Acres $13,450,000 5 States |

| Continental Divide Trail | 17 Tracts 106 Acres 4 Trail Miles $199,300 CO |

1 Tract 2,885 Acres 4 Trail Miles $5,300,000 NM |

None | None | 18 Tracts 2,991 Acres $5,499,300 2 States |

| Florida Trail | 29 Tracts 553 Acres 3 Trail Miles $1,776,674 Florida |

None | None | None | 29 Tracts 553 Acres $1,776,674 |

| Ice Age Trail | None | 6 Tracts 457 Acres $3,780,000 Wisconsin |

None | None | 6 Tracts 457 Acres $3,780,000 |

| New England Trail | None | 12 Tracts 206 Acres 2.5 Trail Miles $4,000,000 CT, MA |

None | None | 12 Tracts 206 Acres $4,000,000 |

| North Country Trail | None | 7 Tracts 395 Acres $2,762,600 WI, PA |

None | None | 7 Tracts 395 Acres $2,762,600 2 States |

| Pacific Crest Trail | 18 Tracts 3,429 Acres $8,039,891+ CA, OR, WA |

None | 16 Tracts 2,843 Acres $1,070,000+ CA, OR |

None | 34 Tracts 6,272 Acres $14,882,151 3 States |

| Total | 70 Tracts 5,256 Acres $14,815,865+ 9 States |

28 Tracts 4,317 Acres $20,192,600 6 States |

16 Tracts 2,843 Acres $1,070,000+ CA, OR |

1 Tract 3,129 Acres $4,300,000 PA |

115 Tracts 15,545 Acres $46,150,725 14 States |

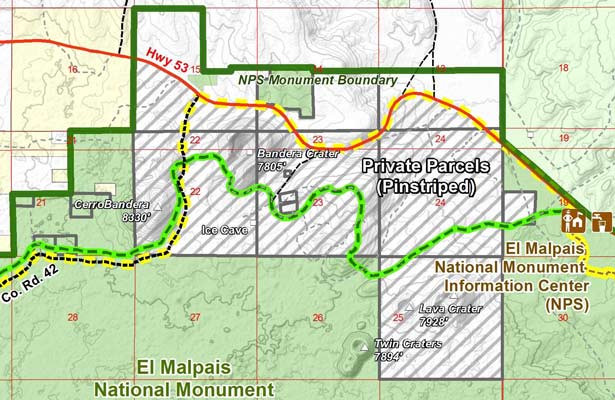

| CDT Proposed Land Buy and Reroute |

|---|

Buying these 2,885 acres for $5.3 million along the CDT in New Mexico would allow a new route (green) off Highway 53 (yellow) and past interesting volcanic features. Development adjacent to El Malpais National Monument would be prevented.

|